Selected Press: (PAGE CONSTRUCTION IN PROGRESS)

June 29, 2023 VARIABLE WEST NEWSLETTER

SIC TRANSIT GLORIA MUNDI (select works by raul j mendez 2008-2023)

Oranj Studio, Portland, OR

April 16 to June 30

This pick is particularly exciting for me because I found it by browsing event listings posted on Variable West! Allow me a brief moment of self congratulation, it's pretty cool when you make a thing and it actually works!

Besides boosting my ego, I'm excited about this whole situation on multiple levels. First, mendez's paintings are excellently weird and I want to look at them for a long time. Any painting with a goat in it makes me think of Marc Chagall, and mendez has a similar vibe but in a much more industrial-capitalist society way. Second, mendez's story is fascinating and I want to know more. He's Venezuelan, graduated from PNCA in 1997, lives in Portland, and supports his art practice by working as a 767 pilot for a shipping company. TELL ME MORE. Third, I wasn't aware of Oranj Studio before this week, and I love their model of an art gallery + hair salon hybrid space.

ArtNet reviews DAY JOB at The Drawing Center

.

The Daily Serving (web)

Chi-Town sharptongued art critic, Pedro Velez, claims to dig a painting

(and tweets it.) (from the 2011 MDW Art Fair)

Posted on Sun, Jul. 04, 2010.

A Quartet of Exhibits in Two Venues Tells Stories in Unexpected Ways

BY BETH DUNLOP

Special to The Miami Herald

GEAN MORENO AND ERNESTO OROZADriftwood provokes with a mass of toilets in a junkyard.There is always an alpha and omega, a beginning and an end. In architecture, as in most arts, the start is the moment made of dreams and fantasy, while the end is often pure degradation. There is a story to be told about it all, if you're willing, and -- as four small exhibitions show us -- the story can be more interesting than the architecture.Two of these shows, both at the Wolfsonian-FIU, are about beginnings, unfulfilled dreams of buildings, and even whole worlds. The other two, at the Miami-Dade Main Library, are about the detritus left behind, in turn transformed into whole new worlds, and new ways of thinking.

`DRIFTWOOD'

Let's start with last things first. Driftwood, a provocative exhibition by Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza in the downtown library auditorium, examines ideas about common unwanted and unappreciated objects and the spaces they occupy, especially junkyards.

The show is surprisingly spare and elliptical, more process than product. Driftwood is a journey of the mind rather than the eye; the show's poster and rack cards offer an image of a sea of toilets in a junkyard -- a refuge for refuse, one might think. But that photo is not on the walls, nor are other junkyard images. Instead, there are screens, one of a wallpaper made by the artists, another showcasing old Miami event posters, both really curiosities leading to the exhibition's two newsprint handouts. The first, titled Thirteen Ways to Look at a Junkyard , is a fascinating meditation on the place of salvage yards in our cities and our society; the other, Freddy, is an intriguing look at the commonplace bucket and the ways in which it can be used to demarcate space or be reused as a chair, stool, table, planter.

`FLORIDA ARCANE'

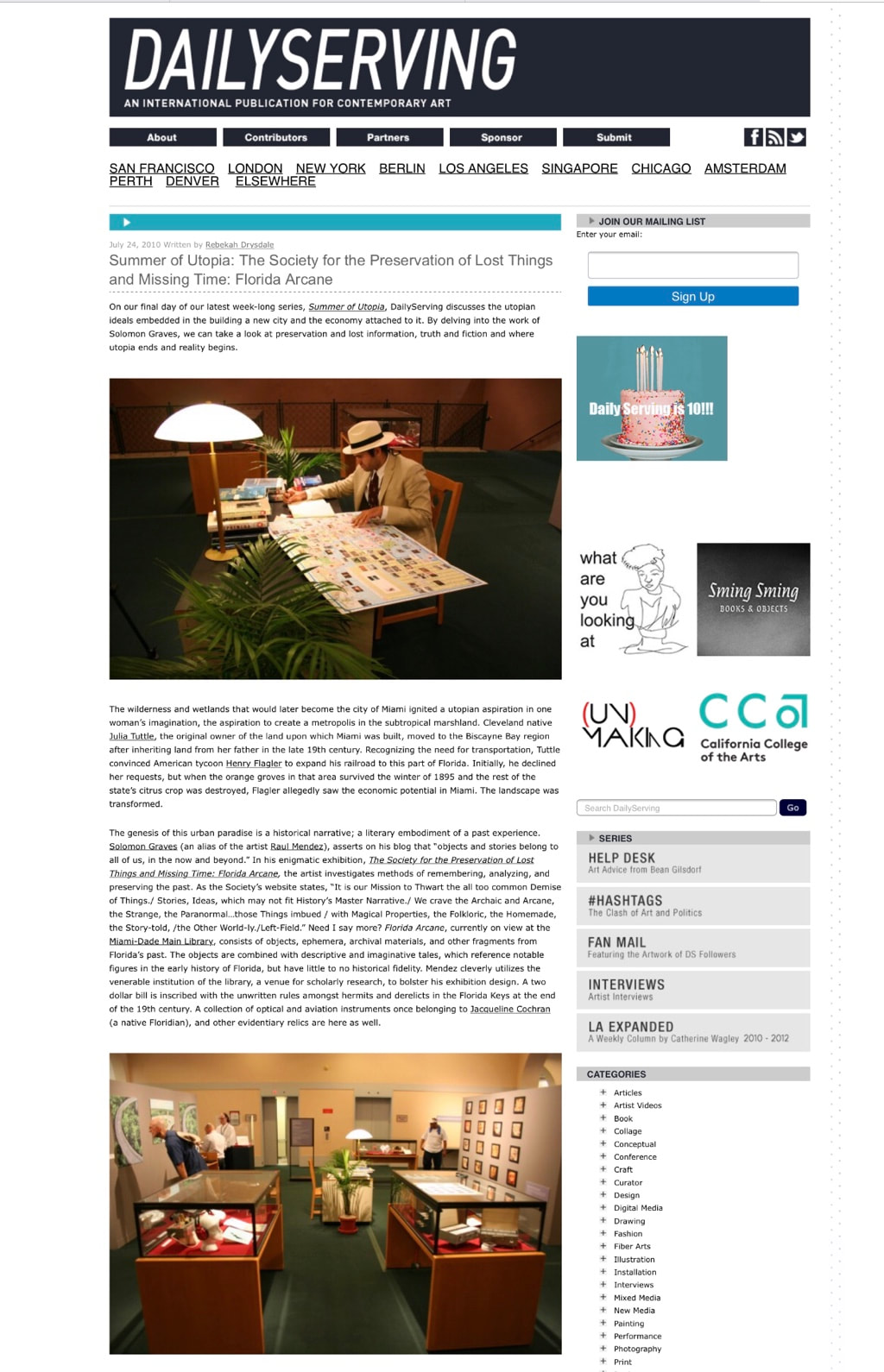

Upstairs at the library (in the interstitial space between the stair landing and the elevators that has long been used as a gallery) is the second show, Raul Mendez's acute, witty and absorbing Florida Arcane (subtitled The Society for the Preservation of Lost Things and Missing Time ). It is almost a shame to discuss this exhibition because there is so much enjoyment (I mean laugh-out-loud humor and actual aha! moments) in seeing it. Suffice it to say that for this work, Mendez has created a doppelganger, Solomon Graves, whom he terms ``Chief Curator, Head Archivist, Executive Director,'' and a set of stories to tell that are fiction verging on the most elusive and imaginative of truths.

To evidence this, simply read the first wall text:

``Sight and Forgotten. / Missing time was recorded and we are witness after the fact. / Its Products Whisper to Us across Timespace. / It is our Mission to Thwart the all too common Demise of Things, / Stories, Ideas, which may not fit History's Master Narrative. / We crave the Archaic and Arcane, the Strange, the Paranormal, / the Outer Edge, the Little Known, those Things imbued / with Magical Properties, the Folkloric, the Homemade, the Story-told, / the Other World-ly./Left-Field.''

Get the idea?

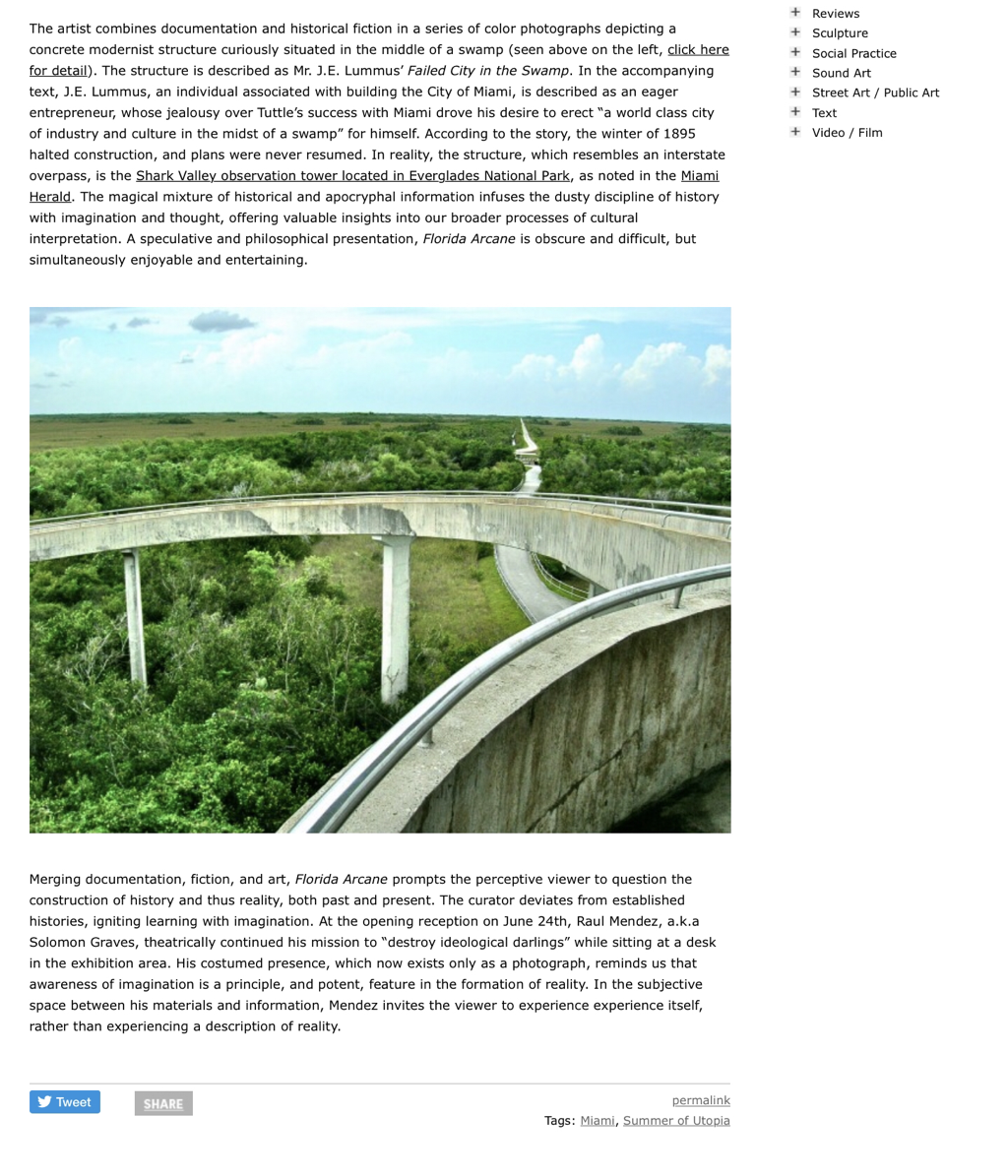

The Florida Arcane collections include a set of glass slides from the Godspeed Airstream Community's trip to Chichen Itza, maps and other ephemera from the aviatrix Jacqueline Cochran, a manmade textile ``tree'' said to be between 600 and 1,200 years old. A high point (literally as well as figuratively) is a series of color photos of a failed Futurist ``city of industry'' in the Okefenokee Swamp that Miami pioneer J. F. Lummus allegedly was attempting to build in 1895 to create ``a portal to the future amongst gators and muck.'' (In fact, just to blow one of the ruses, the images are of the modernist concrete alligator viewing structure at Shark Valley in Everglades National Park.)

The pleasures here come from the mixed metaphors, the fanciful fictions and indeed the quirky, clever objects on view, but Florida Arcane also digs deep into our need to tell stories, to underscore our very existence with narrative. Every place has a tale to tell. And Mendez (a k a Solomon Graves) tells his stories quite brilliantly.

REAL FUTURISM

Ironically, the fake-Futurist ``city of industry'' offers a perfect segue into an exhibition at the Wolfsonian that shows real Futurism. It's a single-gallery show (to wit: also small) mounted in honor of the 100th anniversary of Italian Futurism. A Centennial of Italian Futurism: Selections from the Collection is a precursor to the Wolfsonian's major exhibition, Speed Limits, slated for Sept. 17 through Feb. 20 -- an amuse bouche to the real meal, if you will.

On view are posters, paintings, books and ceramics from the museum's collection, most of them from the 1920s and 1930s when Futurism was not only well established but was beginning to focus on fascist propaganda. That thrust, the use of art for political purposes, is of course a strong underpinning of the Wolfsonian's mission and collection, but taken in sequence with Florida Arcane it is almost startling to see such beauty used for purposes so malevolent. There are moments of greater innocence -- a poster for the Futurist Pantomime Theater and paintings that deal with ideas of design, movement and speed -- all preoccupations of the movement, as well as a portrait of Mussolini and other more politicized works.

ARCHITECTURE

The juxtaposition of good and evil runs through a second exhibition at the Wolfsonian, this one also small and mounted in the foyer of the museum's library. Unrealized Architecture looks at drawings for a range of unrealized projects ranging from the benign -- a house for an art lover that includes a drawing from Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife, Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh, and a social housing project designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1910 -- to the far more ominous, including a large complex called Adolf Hitler-Platz designed in 1941 by Albert Speer and Herman Geisler for the rebuilding of the city of Weimar.

Both idealism and cynicism are in evidence here, even if the idealism at times was in service of ideas and programs we know to be evil, but like the explorations and fictional narratives in Driftwood and Florida Arcane, they tell us a story and make us think deeper, look further at the real and the unreal, the lost hopes and abandoned dreams that come with architecture and the material world.

© 2010 Miami Herald Media Company. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.miamiherald.com

Read more: http://www.miamiherald.com/2010/07/04/v-print/1713058/4-short-journeys-fetchd-a-quartet.html#ixzz1bcaIZXYf

ARTES Y LETRAS

Pepe Mar y Raúl Méndez, reciclaje totémico e instalación fantasmagórica

ALFREDO TRIFF

Especial/El Nuevo Herald

April 28, 2008 Raw Sewage es la última muestra del artista Pepe Mar, en David Castillo Gallery de Wynwood. El show augura una posible dirección para el artista mexicano-americano, cuyo arte se avenía a una escultórica post-pop de figuras tipo espantajo en papel, con colorido bombástico (cercanas al estilo origami), que hace tres años aparecieron en galerías de Wynwood (como el desaparecido Rocket Projects). Obra de estética trash postmoderna que reverbera a ritmo del cómic de los años 90 tardíos, el cult film y la música tecno (fui testigo de algunas figuras totémicas lumínicas de Mar a fines del 2005, en el Miami Light Project).

Las totémicas piezas en Raw Sewage parecieran ''la respuesta estética al despilfarro del capitalismo tardío'' (de acuerdo al crítico Irving Sandler). En el contexto histórico, Mar capta la tradición de uso de materiales pobres, la superposición --aparentemente-- disparatada de un Fausto Melotti (quien anticipara la movida del Arte Povera) y otros artistas recientes como el haitiano Jean Camille Nasson y el japonés Tamoko Takahashi. El material favorito de Mar es la bazofia de plywood, papier-mché, alambres y demás (que en efecto provienen de los escombros de una construcción cercana a la casa del artista en el barrio de Cutler). Cada escultura se sostiene sobre una base con refuerzo de madera que soporta la armadura intermedia terminada en testa antropomórfica (la movida hacia lo abstracto de Mar denota madurez; aunque un par de ojos en una pieza delataban el pasado). El resultado: humor y desamparo.

Caben destacarse piezas como Umbrella, Ella Ella Ella, con atuendo de trenzas colgantes enlazados con retazos de madera y alambrada verde ovillada; Out of Reach Contact Machine, de filigrana metálico-verdosa coronada con antenas rojas; Mama I, figura maternal de tez esmeralda en metonimia con tablas a la cintura y facha alámbrica y Mama 3, dama rebelde exhibiendo coiffure punk, estirado y puntoso. Hay una serie de bustos entre los que se aprecia Lengua: cabezota ambarino anaranjada con indiscreta lengüeta vegetal. Head On usa la misma técnica pero ahora la testa porta semblante amarillo biliar, pelo partido al lado (estilo figurín) con rojo y protuberante narigón.

Raw Sewage (léase

''desagüe'' o ''cloaca'') aunque hábil y distinguida en su ejecución de original teatralidad, revela aún cierto formulismo apoyado en la destreza del artista más que en el flagelo. Masoquismo aparte, toda cloaca requiere de sus demonios.

Twenty Twenty Projects, ubicado en el segundo piso de un edificio corriente, puede pasar inadvertido en los paseos sabatinos nocturnos de Wynwood. Sin embargo, en el último año el pequeño espacio (ahora con aire acondicionado), ha exhibido muestras muy interesantes. En esta ocasión se trata de Negative Space, del artista venezolano-americano Raúl Méndez.

Méndez parece abordar un momento de la pre-modernidad entre mediados y fines del siglo XIX, cuando la ciencia occidental se escinde definitivamente de lo paranormal; circunstancia ideal para la proliferación de sociedades herméticas (como el teosofismo, los rosacruces y la masonería) y de figuras únicas como Madame Blavatsky, Krishnamurti y Rudolf Steiner entre otros.

La muestra es una pista a seguir para un Eugène Franc¸ois Vidocq especializado en lo paranormal. Comienza con Negative Space, pintura oscura que muestra una estancia de dos pisos con sus paredes abiertas a la inspección. Méndez es detallado y artificioso: En el segundo piso se percibe una figura encapuchada de negro frente a un espejo cerca de un clóset repleto de pergaminos enrollados y lienzos de los que cuelga un globo rojo. En el primer piso se observa un librero con lámpara, alfombra y seis escaparates (de altas patas). De ahí sale el cable de una lámpara que ilumina a otra figura encapuchada de blanco. En la parte superior izquierda del cuadro vemos una muchedumbre que conforma una especie de glóbulo del salidero de almas que es la casa. A lo lejos se aprecia una metrópolis.

Méndez recrea en la instalación lo que sugiere en el cuadro: Untitled es un estante pintado de amarillo con dibujos enrollados y el globo rojo (¿déjà vu del clóset en la casa negativa?). The Past and The Pending ocupa el centro de la sala. Sobre un gabinete pintado de blanco hay un vaso colocado sobre un plato (50 fósforos ahogados en su interior atrapan los efluvios del gesto brusco), justo debajo de una lámpara que cuelga del techo (también en la pintura). Al lado del gabinete vemos un video de un incendio, sin duda conectado con la próxima pieza: Little Match Girl's Last es el dibujo escrupuloso de la cabeza de una mujer, un enorme mazo de fósforos sin encender en la boca.

Almost Giunungagap (o la caja de Schopenhauer) es otro video de Méndez que consiste en una caja tocadiscos sobre una silla blanca, colocada delante de la proyección de un video abstracto que ilustra la transformación de un círculo. Por momentos la caja despide una columna de vapor que se esparce por el cuarto creando aspectos ectoplasmáticos (ginungagap parece indicar el vacío entre el fuego y el hielo en la antigua cosmogonía

germánica).

Desde la post-postmodernidad ''negative space'' parece una representación decadente de fin de siglo XIX. El show de Méndez funciona por su imaginación, esmero y balance.•

'Raw Sewage' de Pepe Mar, hasta el 3 de mayo. David Castillo Gallery, 2234 NW 2 Ave., (305) 573-8110. www.castilloart.com.

'Negative Space' de Raúl Méndez, hasta el 3 de mayo, Twenty Twenty Projects, 2020 NW Miami Court, (786) 217-7683, twentytwentyprojects.com/

Pepe Mar y Raúl Méndez, reciclaje totémico e instalación fantasmagórica

ALFREDO TRIFF

Especial/El Nuevo Herald

April 28, 2008 Raw Sewage es la última muestra del artista Pepe Mar, en David Castillo Gallery de Wynwood. El show augura una posible dirección para el artista mexicano-americano, cuyo arte se avenía a una escultórica post-pop de figuras tipo espantajo en papel, con colorido bombástico (cercanas al estilo origami), que hace tres años aparecieron en galerías de Wynwood (como el desaparecido Rocket Projects). Obra de estética trash postmoderna que reverbera a ritmo del cómic de los años 90 tardíos, el cult film y la música tecno (fui testigo de algunas figuras totémicas lumínicas de Mar a fines del 2005, en el Miami Light Project).

Las totémicas piezas en Raw Sewage parecieran ''la respuesta estética al despilfarro del capitalismo tardío'' (de acuerdo al crítico Irving Sandler). En el contexto histórico, Mar capta la tradición de uso de materiales pobres, la superposición --aparentemente-- disparatada de un Fausto Melotti (quien anticipara la movida del Arte Povera) y otros artistas recientes como el haitiano Jean Camille Nasson y el japonés Tamoko Takahashi. El material favorito de Mar es la bazofia de plywood, papier-mché, alambres y demás (que en efecto provienen de los escombros de una construcción cercana a la casa del artista en el barrio de Cutler). Cada escultura se sostiene sobre una base con refuerzo de madera que soporta la armadura intermedia terminada en testa antropomórfica (la movida hacia lo abstracto de Mar denota madurez; aunque un par de ojos en una pieza delataban el pasado). El resultado: humor y desamparo.

Caben destacarse piezas como Umbrella, Ella Ella Ella, con atuendo de trenzas colgantes enlazados con retazos de madera y alambrada verde ovillada; Out of Reach Contact Machine, de filigrana metálico-verdosa coronada con antenas rojas; Mama I, figura maternal de tez esmeralda en metonimia con tablas a la cintura y facha alámbrica y Mama 3, dama rebelde exhibiendo coiffure punk, estirado y puntoso. Hay una serie de bustos entre los que se aprecia Lengua: cabezota ambarino anaranjada con indiscreta lengüeta vegetal. Head On usa la misma técnica pero ahora la testa porta semblante amarillo biliar, pelo partido al lado (estilo figurín) con rojo y protuberante narigón.

Raw Sewage (léase

''desagüe'' o ''cloaca'') aunque hábil y distinguida en su ejecución de original teatralidad, revela aún cierto formulismo apoyado en la destreza del artista más que en el flagelo. Masoquismo aparte, toda cloaca requiere de sus demonios.

Twenty Twenty Projects, ubicado en el segundo piso de un edificio corriente, puede pasar inadvertido en los paseos sabatinos nocturnos de Wynwood. Sin embargo, en el último año el pequeño espacio (ahora con aire acondicionado), ha exhibido muestras muy interesantes. En esta ocasión se trata de Negative Space, del artista venezolano-americano Raúl Méndez.

Méndez parece abordar un momento de la pre-modernidad entre mediados y fines del siglo XIX, cuando la ciencia occidental se escinde definitivamente de lo paranormal; circunstancia ideal para la proliferación de sociedades herméticas (como el teosofismo, los rosacruces y la masonería) y de figuras únicas como Madame Blavatsky, Krishnamurti y Rudolf Steiner entre otros.

La muestra es una pista a seguir para un Eugène Franc¸ois Vidocq especializado en lo paranormal. Comienza con Negative Space, pintura oscura que muestra una estancia de dos pisos con sus paredes abiertas a la inspección. Méndez es detallado y artificioso: En el segundo piso se percibe una figura encapuchada de negro frente a un espejo cerca de un clóset repleto de pergaminos enrollados y lienzos de los que cuelga un globo rojo. En el primer piso se observa un librero con lámpara, alfombra y seis escaparates (de altas patas). De ahí sale el cable de una lámpara que ilumina a otra figura encapuchada de blanco. En la parte superior izquierda del cuadro vemos una muchedumbre que conforma una especie de glóbulo del salidero de almas que es la casa. A lo lejos se aprecia una metrópolis.

Méndez recrea en la instalación lo que sugiere en el cuadro: Untitled es un estante pintado de amarillo con dibujos enrollados y el globo rojo (¿déjà vu del clóset en la casa negativa?). The Past and The Pending ocupa el centro de la sala. Sobre un gabinete pintado de blanco hay un vaso colocado sobre un plato (50 fósforos ahogados en su interior atrapan los efluvios del gesto brusco), justo debajo de una lámpara que cuelga del techo (también en la pintura). Al lado del gabinete vemos un video de un incendio, sin duda conectado con la próxima pieza: Little Match Girl's Last es el dibujo escrupuloso de la cabeza de una mujer, un enorme mazo de fósforos sin encender en la boca.

Almost Giunungagap (o la caja de Schopenhauer) es otro video de Méndez que consiste en una caja tocadiscos sobre una silla blanca, colocada delante de la proyección de un video abstracto que ilustra la transformación de un círculo. Por momentos la caja despide una columna de vapor que se esparce por el cuarto creando aspectos ectoplasmáticos (ginungagap parece indicar el vacío entre el fuego y el hielo en la antigua cosmogonía

germánica).

Desde la post-postmodernidad ''negative space'' parece una representación decadente de fin de siglo XIX. El show de Méndez funciona por su imaginación, esmero y balance.•

'Raw Sewage' de Pepe Mar, hasta el 3 de mayo. David Castillo Gallery, 2234 NW 2 Ave., (305) 573-8110. www.castilloart.com.

'Negative Space' de Raúl Méndez, hasta el 3 de mayo, Twenty Twenty Projects, 2020 NW Miami Court, (786) 217-7683, twentytwentyprojects.com/

New American Paintings Issue 64, 2007

Principal Juror – Trevor Richardson, Director, Herter Art Gallery, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Editor's Comments - In this current issue of New American Paintings, we are presented with the work of forty artists for whom the practice of painting and drawing as a means of developing ideas and images is a common characteristic. Through their investigation of the aesthetic and conceptual possibilities of image making on a two-dimensional surface, they have demonstrated an impressive range of intellectual interests and formal concerns that serves to emphasize the multi-faceted nature of contemporary visual culture. The result, one hopes, is a collection of compelling works that will help underscore the continuing role of painting and drawing as a vital and provocative vehicle for artistic experience.

Inevitably in a body of work of this kind, where the principal focus is directed at the artists of a particular region (in this case the south-east), there is a tendency to look for patterns, traits, or distinguishing characteristics which collectively serve to define the artistic practice that takes place there, setting it apart from other regions of the country. If such characteristics do indeed exist, I was unable to detect them here. However, if the final selection does have a certain coherence and identity despite the broad range of work it encompasses, it is not because it defines anything (a group, a school, or particular trend), but rather because it reflects something––namely a set of attitudes that address themselves in different ways to the depiction of space.

This, of course, should not be surprising. Space is an extremely important component of our physical experience in the world. It presents us with a set of basic polarities for organizing frameworks of perception and the psychological effects they invoke. It represents a continuously contested territory over which private and public interests meet or diverge. It constitutes a habitat for behavior patterns and rituals, as well as a setting for stories and interests, individual and communal, deriving from these considerations. These have gained purchase on the intellect and imagination and have remained a more or less constant theme in Western art from antiquity to the present day.

An example of this impulse may be found in the work of Raul J. Mendez, who employs landscape as both the setting and context for his whimsical and eccentric paintings. Vexingly placeless, they make a direct appeal to our capacity to project ourselves imaginatively, inviting us along on journeys across vast desolate tundras, peopled by tiny figures engaged in deadpan, and often cruelly humorous, scenes. There is a distinct undercurrent of melancholy in his paintings, mediating as they do the often disturbing condition of interpersonal human relationships––especially between groups or communities. Similarly, Ian Brownlee employs landscape as a device to capitalize on our basic impulse to weave images into narrative. In his paintings, the use of perspective to create an unexpectedly dramatic spatial illusion permits us entry into what appears to be an independently existent and self-sufficient “world” located neither in the past nor the present, but always slightly out of reach and continually open to interpretation.

A somewhat different conception of space is evident in the drawings of David Bailin. Here, instead of being confronted with a vast panorama in which diminutive figures are seen to grapple with their fate, we are presented with austere, claustrophobic, uncertain rooms in which neither time nor place is fixed. The psychologically-charged interior spaces, such as in the drawing “Apparition,” serve as the context or “stage” within which Bailin’s solitary figures appear engaged in the enactment of some private ritual, the precise meaning of which is left deliberately open ended. Jeremy Hughes is another artist whose depiction of interior space has a decidedly introspective quality, one that invites speculative interest on the part of the viewer as to its meaning. In paintings such as “Men’s Room,” the grip on our psyche is achieved, in part, through the artist’s ability to engage the viewer’s emotions, memory, and intellect, holding them in a tense and surreal suspension, which can only be read and deciphered through associations related to, or implemented in, the mystery created by the artist.

Many painters have found in architecture a “stage” or “space” with which they can experience the physicality of boundaries, of exits and entrances, of penetration and resistance, of its axial relation to the up and down. Such concerns are paramount in the work of Judy Rushin, who seems preoccupied by motifs that allude to architectural structures––particularly those used to identify and inflect the movement of open planes and spaces. In “Doing Nothing at the Zoo,” for example, the appeal resides in the visual tension that is created through an uneasy coexistence between the “abstract” and the “real,” which, coupled with an abrasive physicality, adds a semantic and iconographic richness to the image. Like Rushin, the paintings of Julio Garcia also refer to architecture, but in a more restricted way. In “Anywhere America No. 1,” Garcia annexes the formal vocabulary of architectural drawing, particularly diagrams of city plans with their rows of orderly gridded streets, and uses them as the basis for extrapolating a series of flat, irregular, abstract shapes that somehow manage to acquire a mysterious new meaning and purpose. For conceptional abstractionists such as Garcia, the task is to infuse old modernist forms––such as the grid––with new content, reinvigorating anachronistic non-objective form by re-objectifying it, indeed, humanizing it––making it once again emotionally vital and resonant.

One of the major currents, which informed American landscape painting in the nineteenth century, was the cult of the sublime. The sublime came to represent what appeared as awesome in its grandeur and immensity, and the overall effect that those qualities came to exert on the viewer’s sensory responses. Something of the historical associations that have attached themselves to notions of “the sublime,” together with the “near-surreal,” persists in Caomin Xie’s precisely rendered yet thematically elusive paintings. In “Still Image 106, Fog on Ocean,” the process of meditative concentration combined with a painstaking precision enables the artist to achieve a strange conceptual distance that, paradoxically, renders his painted seascape less real and more abstract.

A more prosaically descriptive conception of “landscape” is offered to us in Alan Ludwig’s “Mountain View.” Here, Ludwig invites the viewer to participate in an experience of landscape that finds expression in a graphic language characterized by a reserved and formal elegance. Despite its apparent austerity, Ludwig’s work embodies a rich poetics of place, which, through a process of distillation, achieves a measured ritualistic deliberation that insulates us from any easy, romantic union with nature.

In its more refined form, the genre of still-life painting calls for a recognition of the object in terms other than a mere physical thing or its more or less convincing imitation. These attributes are apparent in Joanna Catalfo’s painting, “Camera and Calla Lilies,” where the relative oddity of the juxtaposition, coupled with the centrality of their placement, confers upon the objects an enhanced importance. The dry and exact pleasure with which Catalfo’s paint covers the surface, its luminosity, even its neatness, creates a feeling of preciousness which further contributes toward the feeling that we are in the presence of something unreal or slightly mystical. Markedly different in spirit and conception is “Reichenbach Porcelain,” a still-life painting by Hooper Turner. Here, the artist employs the media’s weapons of persuasive words and pictures as a vehicle for a subversive post-modernist sensibility, in which a precise realism is combined with bowdlerized textual overlay, to imbue the painting with a feeling of unease, anxiously at odds with the bland images of middle-class consumer culture it depicts.

The unique capacity of abstract painting to excite an ideational and emotional response not only on the retina, but which also inheres in the mind, continues to provide a powerful source of inspiration for many artists. These attributes are manifest in the work of Sarah Sharpe, whose paintings are about feeling and the ways in which feeling can nourish formal and informal relationships. They are also about color and the ways in which certain shapes summon certain colors. The passage of time, as well as a feeling of transience, is eloquently expressed through the artist’s command of her medium and its transformative powers. Jennifer Palmer and Erin McIntosh have also evolved a highly personal mode of expression within the syntax of contemporary abstract painting. Their works are filled with dichotomies, with tensions that are psychological as well as physical. They abound with the marks of bodily involvement in the process of painting, with their sheer physicality initially demanding a visceral and intuitive, rather than a strictly intellectual reaction.

In conclusion, I would like to state that I was pleased with the standard of the work submitted. As juror, I made a conscious effort to ensure that my judgments remained as disinterested as possible. However I suspect that some, inevitably, were the result of subjective preferences. One also had to contend with the problem of making decisions based upon slides, a photographic medium which at times can be notoriously unreliable in terms of its ability to accurately record the visual characteristics of art objects. My commiserations therefore go to those artists who did not make the final cut––but there will be other contests and other jurors.

Principal Juror – Trevor Richardson, Director, Herter Art Gallery, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Editor's Comments - In this current issue of New American Paintings, we are presented with the work of forty artists for whom the practice of painting and drawing as a means of developing ideas and images is a common characteristic. Through their investigation of the aesthetic and conceptual possibilities of image making on a two-dimensional surface, they have demonstrated an impressive range of intellectual interests and formal concerns that serves to emphasize the multi-faceted nature of contemporary visual culture. The result, one hopes, is a collection of compelling works that will help underscore the continuing role of painting and drawing as a vital and provocative vehicle for artistic experience.

Inevitably in a body of work of this kind, where the principal focus is directed at the artists of a particular region (in this case the south-east), there is a tendency to look for patterns, traits, or distinguishing characteristics which collectively serve to define the artistic practice that takes place there, setting it apart from other regions of the country. If such characteristics do indeed exist, I was unable to detect them here. However, if the final selection does have a certain coherence and identity despite the broad range of work it encompasses, it is not because it defines anything (a group, a school, or particular trend), but rather because it reflects something––namely a set of attitudes that address themselves in different ways to the depiction of space.

This, of course, should not be surprising. Space is an extremely important component of our physical experience in the world. It presents us with a set of basic polarities for organizing frameworks of perception and the psychological effects they invoke. It represents a continuously contested territory over which private and public interests meet or diverge. It constitutes a habitat for behavior patterns and rituals, as well as a setting for stories and interests, individual and communal, deriving from these considerations. These have gained purchase on the intellect and imagination and have remained a more or less constant theme in Western art from antiquity to the present day.

An example of this impulse may be found in the work of Raul J. Mendez, who employs landscape as both the setting and context for his whimsical and eccentric paintings. Vexingly placeless, they make a direct appeal to our capacity to project ourselves imaginatively, inviting us along on journeys across vast desolate tundras, peopled by tiny figures engaged in deadpan, and often cruelly humorous, scenes. There is a distinct undercurrent of melancholy in his paintings, mediating as they do the often disturbing condition of interpersonal human relationships––especially between groups or communities. Similarly, Ian Brownlee employs landscape as a device to capitalize on our basic impulse to weave images into narrative. In his paintings, the use of perspective to create an unexpectedly dramatic spatial illusion permits us entry into what appears to be an independently existent and self-sufficient “world” located neither in the past nor the present, but always slightly out of reach and continually open to interpretation.

A somewhat different conception of space is evident in the drawings of David Bailin. Here, instead of being confronted with a vast panorama in which diminutive figures are seen to grapple with their fate, we are presented with austere, claustrophobic, uncertain rooms in which neither time nor place is fixed. The psychologically-charged interior spaces, such as in the drawing “Apparition,” serve as the context or “stage” within which Bailin’s solitary figures appear engaged in the enactment of some private ritual, the precise meaning of which is left deliberately open ended. Jeremy Hughes is another artist whose depiction of interior space has a decidedly introspective quality, one that invites speculative interest on the part of the viewer as to its meaning. In paintings such as “Men’s Room,” the grip on our psyche is achieved, in part, through the artist’s ability to engage the viewer’s emotions, memory, and intellect, holding them in a tense and surreal suspension, which can only be read and deciphered through associations related to, or implemented in, the mystery created by the artist.

Many painters have found in architecture a “stage” or “space” with which they can experience the physicality of boundaries, of exits and entrances, of penetration and resistance, of its axial relation to the up and down. Such concerns are paramount in the work of Judy Rushin, who seems preoccupied by motifs that allude to architectural structures––particularly those used to identify and inflect the movement of open planes and spaces. In “Doing Nothing at the Zoo,” for example, the appeal resides in the visual tension that is created through an uneasy coexistence between the “abstract” and the “real,” which, coupled with an abrasive physicality, adds a semantic and iconographic richness to the image. Like Rushin, the paintings of Julio Garcia also refer to architecture, but in a more restricted way. In “Anywhere America No. 1,” Garcia annexes the formal vocabulary of architectural drawing, particularly diagrams of city plans with their rows of orderly gridded streets, and uses them as the basis for extrapolating a series of flat, irregular, abstract shapes that somehow manage to acquire a mysterious new meaning and purpose. For conceptional abstractionists such as Garcia, the task is to infuse old modernist forms––such as the grid––with new content, reinvigorating anachronistic non-objective form by re-objectifying it, indeed, humanizing it––making it once again emotionally vital and resonant.

One of the major currents, which informed American landscape painting in the nineteenth century, was the cult of the sublime. The sublime came to represent what appeared as awesome in its grandeur and immensity, and the overall effect that those qualities came to exert on the viewer’s sensory responses. Something of the historical associations that have attached themselves to notions of “the sublime,” together with the “near-surreal,” persists in Caomin Xie’s precisely rendered yet thematically elusive paintings. In “Still Image 106, Fog on Ocean,” the process of meditative concentration combined with a painstaking precision enables the artist to achieve a strange conceptual distance that, paradoxically, renders his painted seascape less real and more abstract.

A more prosaically descriptive conception of “landscape” is offered to us in Alan Ludwig’s “Mountain View.” Here, Ludwig invites the viewer to participate in an experience of landscape that finds expression in a graphic language characterized by a reserved and formal elegance. Despite its apparent austerity, Ludwig’s work embodies a rich poetics of place, which, through a process of distillation, achieves a measured ritualistic deliberation that insulates us from any easy, romantic union with nature.

In its more refined form, the genre of still-life painting calls for a recognition of the object in terms other than a mere physical thing or its more or less convincing imitation. These attributes are apparent in Joanna Catalfo’s painting, “Camera and Calla Lilies,” where the relative oddity of the juxtaposition, coupled with the centrality of their placement, confers upon the objects an enhanced importance. The dry and exact pleasure with which Catalfo’s paint covers the surface, its luminosity, even its neatness, creates a feeling of preciousness which further contributes toward the feeling that we are in the presence of something unreal or slightly mystical. Markedly different in spirit and conception is “Reichenbach Porcelain,” a still-life painting by Hooper Turner. Here, the artist employs the media’s weapons of persuasive words and pictures as a vehicle for a subversive post-modernist sensibility, in which a precise realism is combined with bowdlerized textual overlay, to imbue the painting with a feeling of unease, anxiously at odds with the bland images of middle-class consumer culture it depicts.

The unique capacity of abstract painting to excite an ideational and emotional response not only on the retina, but which also inheres in the mind, continues to provide a powerful source of inspiration for many artists. These attributes are manifest in the work of Sarah Sharpe, whose paintings are about feeling and the ways in which feeling can nourish formal and informal relationships. They are also about color and the ways in which certain shapes summon certain colors. The passage of time, as well as a feeling of transience, is eloquently expressed through the artist’s command of her medium and its transformative powers. Jennifer Palmer and Erin McIntosh have also evolved a highly personal mode of expression within the syntax of contemporary abstract painting. Their works are filled with dichotomies, with tensions that are psychological as well as physical. They abound with the marks of bodily involvement in the process of painting, with their sheer physicality initially demanding a visceral and intuitive, rather than a strictly intellectual reaction.

In conclusion, I would like to state that I was pleased with the standard of the work submitted. As juror, I made a conscious effort to ensure that my judgments remained as disinterested as possible. However I suspect that some, inevitably, were the result of subjective preferences. One also had to contend with the problem of making decisions based upon slides, a photographic medium which at times can be notoriously unreliable in terms of its ability to accurately record the visual characteristics of art objects. My commiserations therefore go to those artists who did not make the final cut––but there will be other contests and other jurors.